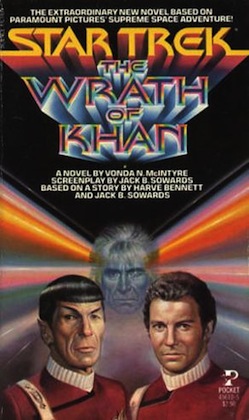

Vonda McIntyre’s novelization of The Wrath of Khan was originally published in 1982. I picked up a used copy last month, at Pandemonium in Central Square in Cambridge.

I’ve read it before—Khan and I are past the point in our relationship where we can surprise each other. But it didn’t matter. Reading on the T, I rode two stops past South Station, had to get off at Andrew station to go back, and missed my train home.

I’m a sucker for character moments, and while McIntyre is constrained by the parameters of the film here, she finds space for a lot of moments in her opening chapters: Saavik’s argument with Kirk about morality; Spock’s fascination with origami so advanced it is indistinguishable from technology; McCoy’s depressing attempt to get Kirk drunk for his birthday. While all this is going on, Chekov is looking for a lifeless planet and accidentally rediscovering Khan.

There are several reasons this sucks for Chekov. The first is that Khan informs him that Marla McGivers, former historian to the USS Enterprise, is dead.

I always thought McGivers was a bad historian, partly because Kirk didn’t respect her, and partly because her quarters were full of watercolor portraits of manly dictators. These implied that she was well behind the cutting edge of history even for the decade she was written in, never mind the decade of her fictional existence. Manly dictators are 19th century historiography. I have always felt the Federation’s historians should be well versed on the work of the Annales School, particularly their work on mentalités, and the Marxist historians, and possibly some of the post-modern analyses that were emerging in the 60s. If McGivers had been, she might have opted out of leaving the ship to settle a new planet with a known criminal.

The risk assessment involved doesn’t really require a history degree—a passing familiarity with Little House on the Prairie would have done the trick. Either McGivers didn’t know about the risks of dying horribly of something like a cerebral infestation of sandworms, or her love is so strong she didn’t care. But the controversy is moot, because she is dead. Khan is sad, which is why he has a tank of sandworms handy for any Federation representatives who happen to drop by. Chekov is sad, because he had a crush on McGivers, and now he also has sandworms in his helmet.

The rest of the story is pretty miserable for Chekov, as he is forced to betray everyone he cares about. Since he’s never had much in the way of family and is notoriously unlucky in love, this means Khan forces him to betray Kirk and help lay a trap for the Enterprise. Since the Federation is really very small, this trap also draws in Carol Marcus, Kirk’s ex, and his son who are working on the Genesis project. Chekov is only the earliest exponent of Khan’s misery. Scottie’s nephew, a Wesley Crusher prototype who has a crush on Saavik, dies of coolant poisoning after a long struggle to earn his uncle’s respect. Almost the entire Genesis Project research staff, including a pair of Deltans and the quirky guys who also make video games, are tortured to death. Everyone has someone to lose, and all of those people are doomed. The sheer volume of the casualties could lead a reader to depersonalize them. McIntyre makes these people you barely knew into characters you greatly miss.

Kirk has already lost his ex, and he’s never really known his son, and if you haven’t heard it somewhere in the thirty-two years since the film was released, I don’t feel bad telling you that his loss is Spock. Spock’s death comes at the very end, where there is no hope of fixing it. The universe is out of joint, and we have to wait for the next book to set it right.

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.